normally of several different nationalities and they had their

bunks in the deck house at the foremast.

Only a few primitive places were visited on the journey

for unloading and loading, and the period at sea between

the individual landfalls could last for several months, with

all the problems this could lead to in terms of lack of or

poor provisions, personal quarrels among the crew, or be-

tween officers and men. The latter, however, generally only

occurred on land, when alcohol gained the upper hand. Ac-

cidents, sickness and desertion necessitated taking on new

people in foreign ports. And when the ship finally, after at

least a year at sea, concluded its journey and returned to

Europe, the crew was discharged for immediate disembar-

kation when the ship was moored.

The following were done before the ship reached the

harbour. The pilot was normally the first “foreign” man on

board. Later came a connection to a tugboat and so – while

the ship was still sailing – a veritable invasion of tradesmen,

crimps, Harpies, loose women and many more, all nurturing

a burning desire to help the sailors spend their hard-earned

pay. When finally the ship was moored, the crew members

went ashore with their possessions, but without money in

their pockets. Payment for their time was not made until the

following day or even later, at the office of a Danish con-

sul. In the meantime, the crimps offered prompt food and

lodging on credit and just as happily advanced money so the

reunion with the dry land could be celebrated, and a proper

goodbye to shipmates could be said.

After settling of accounts at the consul’s, the crimp got

the money he had advanced and happily offered to look af-

ter and ration the rest of the money so it could last until the

next hiring on board a vessel. After the ship was once again

ready to depart, the captain went to the crimp to hire his next

crew. Those who had spent all the money they had saved and

received a favourable advance were first in line. Borrowing

money was not free. The crimp was generously paid with

an allotment note for one or two months of the individual

sailor’s future wages. This meant that he crimp had noth-

ing to worry about because the allotment note fell due for

immediate payment when the ship had made its departure.

In the 1890s the British tried to create rules for the mini-

mum number of men to sail the ships safely, but the rules

were not generally applied. Under Danish maritime law,

the captain was responsible for ensuring that the ship was

properly manned. A comparison between the British ideal

number and the Danish ships’ actual number of sailors

shows that Danish ships normally sailed a few men short.

There were no rules on hours of work. The crew on the Dan-

ish ships was divided into two watches, each of which had

three watches of four hours during a 24 hour period, and

each duty team had a further two hours of duty a day, so

the actual working time was 14 hours a day. When all men

were needed on deck, it was not subsequently possible to

make up for the lost leisure and sleep, and there was no such

thing as payment for overtime. If the ship lost a man during

the journey, the crew could, however, claim shares of the

missing man’s payment.

This did not change in the “Iron Age” where – despite

the harsh conditions – there were enough people to sail the

ships.

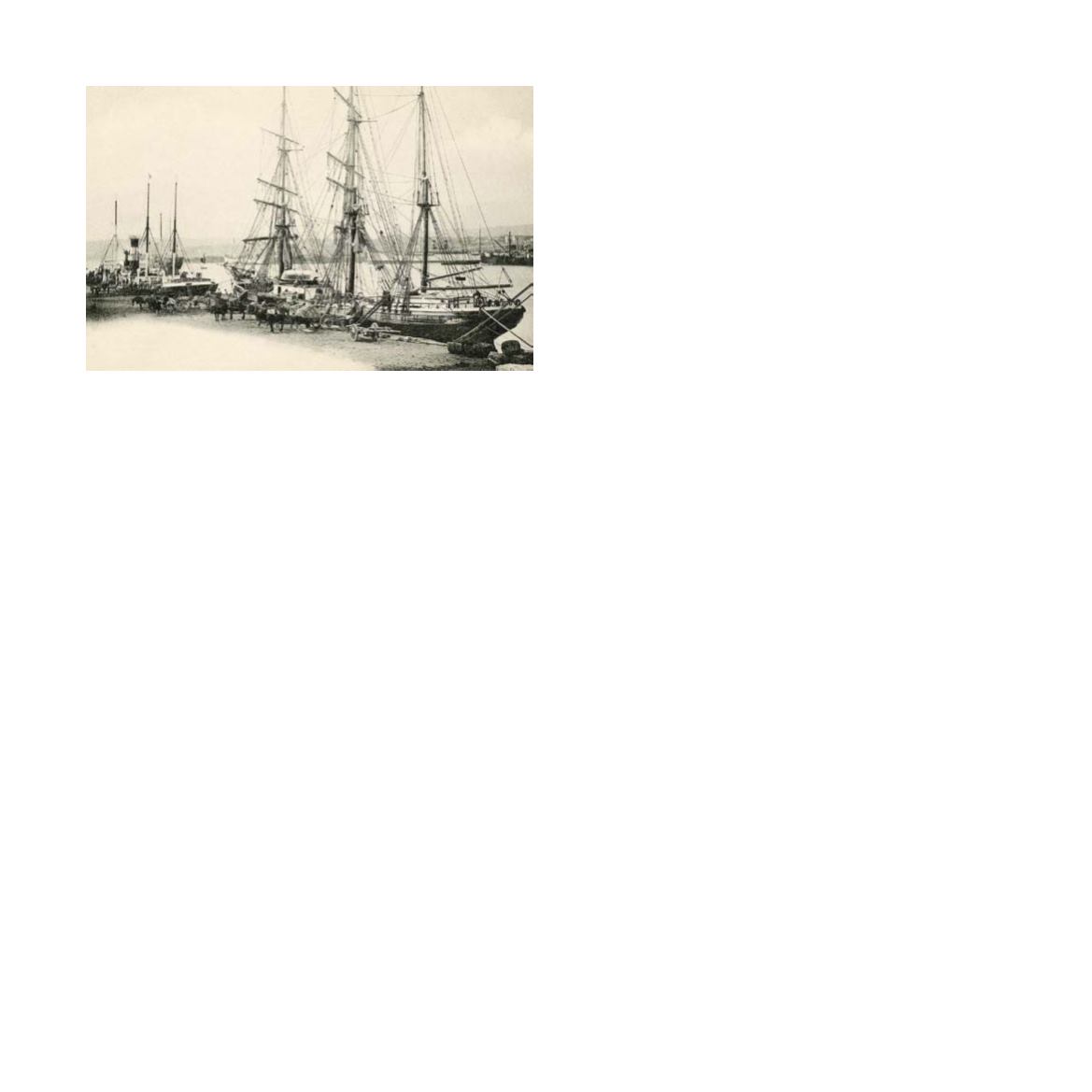

Ældre bark losser i Marseille omkring år 1900. Adskillige

storsejlere sluttede deres rundrejser i den store havneby. Men der

var langt mellem nye hyrer til afmønstrede søfolk, hvorfor mange

- for egen regning - rejste nordpå til Antwerpen eller Rotterdam

for her at finde ny hyre, men først måtte de i logi for at oparbejde

gæld. Postkort: Holger Munchaus Petersens samling.

55